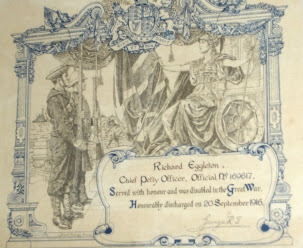

The certificate in the second photo hangs in my sitting room: it is the honourable discharge certificate issued to my paternal grandfather, one of many signed by King George V and handed out to the maimed of World War 1. Blinded at the

Battle of Jutland, my grandfather never saw his son, my father. A career naval officer, he had travelled far and wide; I remember , as a child, our house being filled with silks and artefacts he had brought from China, until they just wore away or got broken over time. I like to think that he visited Sicily and felt the sun on his face before the darkness engulfed him. Before moving here, I considered giving the certificate to the Maritime Museum in Swansea – they had expressed some interest in having it – but I just couldn’t let it go.

I thought about telling this story on November 11th but did not, [a] because there is no commemoration here on that day and [b] because although I of course respect and feel deeply for my fallen or wounded countrymen in any war, I have issues with the current war and so felt it best to remain silent. I am not, I would like to point out, a pacifist; I should be but I am not. I will now break that silence in view of what happened at the weekend:

Many of my fellow-

Blogpowerers were

incensed at this and I understand their anger.

Daily Referendum,

James,

Cllr Tony Sharp and

Lord Nazh all posted on it immediately [I apologise if I have left anyone out] and I agree with much of what they have to say. James said, “I would dearly love to see some sort of post, some sort of comment from the womenfolk to assure me we haven’t gone stark, raving mad.” I commented on his site; now here is the post, though I’m not sure you are going to like it, James.

According to the report, a woman, or two women, behaved abusively towards badly injured servicemen using an area of her/their local swimming pool as part of their rehabilitation. That is, of course, appalling and I am not in any way excusing the women. Indeed, I hope that, had I been there, I would have had the courage to challenge them. But I would not have asked them “What have you ever done for your country?” Instead, I would have tried to find out what exactly their reasons were and would have tried to remonstrate with them. I am not for a moment suggesting that I would have done this totally calmly as I would have been angry, too. I would probably have got myself

beaten up or worse, in today’s Britain. Much has been written about the fact that it was women who behaved in this way: yet I can imagine, because I have witnessed similar behaviour, that it could have come from young men, too. The most likely reason for their behaviour is, I believe, sheer ignorance. I would be willing to bet that they would have made similar remarks to any group of disabled people, and I would have been just as incensed: I hope my fellow-Blogpowerers would have been, too.

I have read that in the USA, the women would have been immediately taken to task in no uncertain terms and there are three possible reasons why this apparently did not happen in Britain: [1] maybe there just weren’t many people about [2] those who were about feared for their jobs or violent consequences [both of which suggest sad truths about our society] and [3] we just do not have the unquestioning patriotism of Americans. We do not put our hands on our hearts the minute the chords of our National Anthem strike up and I, for one, will stand for

Mae Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau but will not rise for

God Save the Queen [ or at least, there are very few occasions when I would]. I think this questioning society is, on the whole, a good development and one of the quotes I liked to leave my A level students with was this, from

Winifred Holtby’s South Riding:

“Question everything – even what I’m saying now. Especially, perhaps, what I say. Question everyone in authority, and see that you get sensible answers to your questions.”

I never read them the next part, because it would not have been appropriate, but I think it is worth quoting here:

“Vow as much love to your country as you like; serve to the death if that is necessary… But, I implore you, do not forget to question.”

Without questioning, there would have been no resistance at all to tyrants through the ages.

Let us not confuse questioning, however, with lack of deference, which is probably a good thing, and lack of respect, which is not. Yet I cannot agree with James that our troops deserve, at all times, unquestioning respect: for if that is so, I would be required to respect those who had done

this. General Montgomery, I read, regarded rape as a mere by-product of war; how can I respect that or “teach” others to do so?

James also asks, in the comments, whether women could just say “Thank you to our brave men who fought to protect us" without bringing feminism into it: I’ll leave aside the feminist issue but would point out that women have always been both the victims and complicit in war: wives and mothers of sons waited in dread for the telegrams in both World Wars, just as they dread the

appearance at the door of the officer in a suit today, whilst in WW1 some women were as fooled by the propaganda as their menfolk, and, in giving out white feathers to non-combatants and generally egging the men on, were as responsible as their government for encouraging the whole bloody mess. In both wars, there were unsung heroines and today women are also front line soldiers. So it is no longer possible to conjure up an image of the “little woman at home who couldn’t defend herself”.

When the

shelling on the western front stopped on Xmas Eve, 1914, and both sides saw sense and played football instead of slaughtering each other, I suspect that the reaction of many women was, “If they can lay down arms for an hour or two, why can’t they stop the entire war?” and I don’t think this thought was far from the minds of many combatants either. Or, as John Lennon and others were later to put it, “

What if they gave a war and nobody came?” If only!

I do not believe, you see, that going to war always makes your country – or, god forbid, someone else’s – a “safer place”. Wars have been and are being fought over language, territory, the colour of people’s skin, slavery, oil, an abstract noun and, most often, the ambitions of unscrupulous politicians who never get near the firing line. Remember the reactions of the politicians in

Fahrenheit 9/11 when Michael Moore suggests they sign their own sons and daughters into the military? “No way!” their faces said.

Only very rarely is war really fought for “freedom” and when it is, it seems to me, those in power and their supporters do not seem very keen upon upholding the freedom to dissent, or to abhor war: I have been criticised in Britain, in November, our season of remembrance, for wearing a white peace poppy along with the red remembrance one. Yet I often think of the blind sailor who never saw his son and my way of respecting and remembering him and those like him is to campaign for peace.